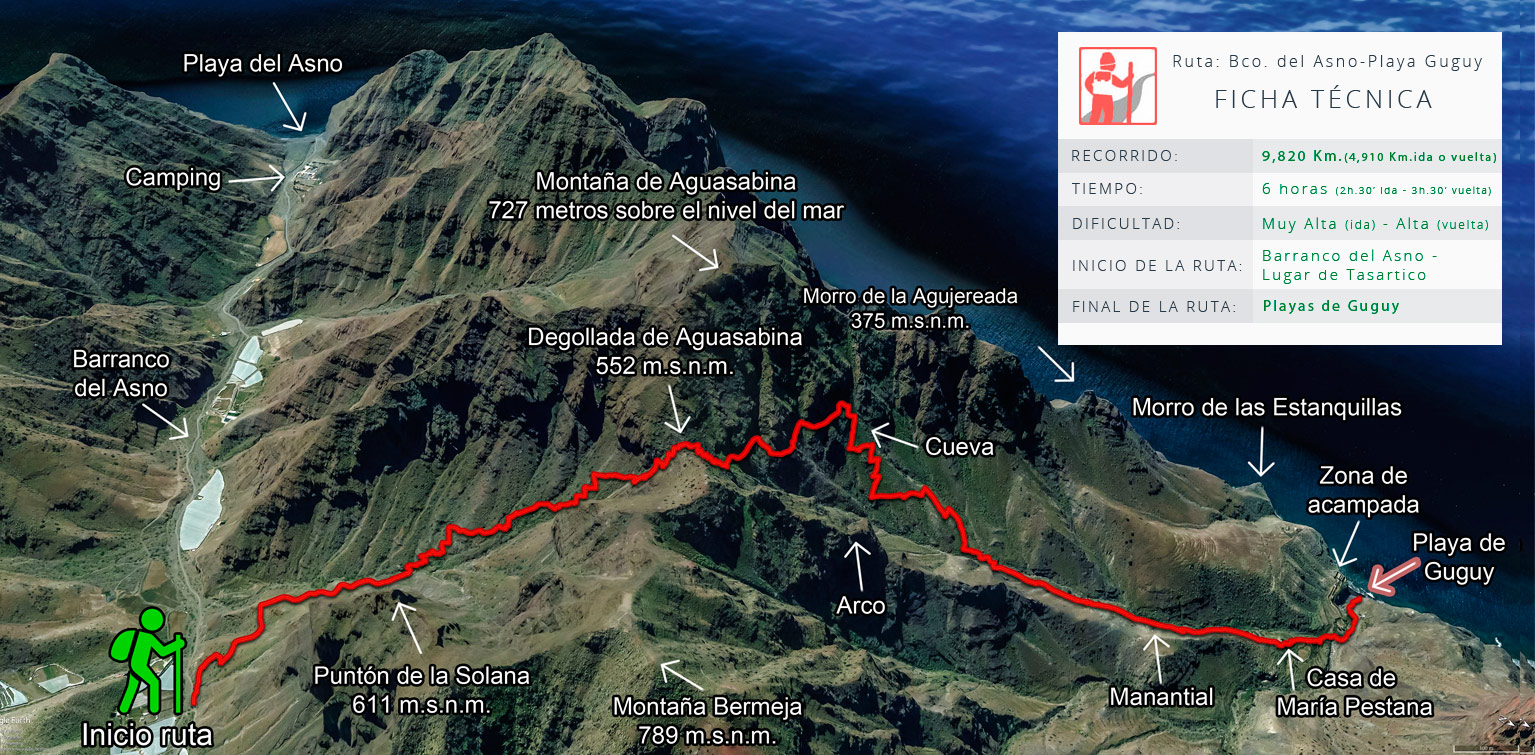

ROUTE DESCRIPTION – Tasartico (Bco. del Asno) – Playas de Guguy (Güi Güi)

GüiGüi, or Guguy for the locals, is located within the “Güigüi Special Natural Reserve”, one of the most remote and inaccessible places on the island of Gran Canaria. Surrounded by mountain crests that rise up to nearly 1,000 metres in height, access is only possible to its beaches by boat or along footpaths.

This stunning route is only suitable for people who enjoy making a great physical effort during the walk, as we are talking about a route that is wild, uninhabited, and indeed, as spectacular is it startling.

Therefore, before visiting this enclave all hikers need to assess and consider not only their physical fitness, but also the time of year they wish to tackle this route, and of course, the prevailing weather conditions. It is recommended, or essential even, to start this route just before dawn, as if the day is going to be a hot one, the tough surroundings make it dangerous under the hot temperatures due to the lack of shelter and the risk of sunstroke is very high. If you are in the company of an experienced guide, then it is best to set out before daylight.

This is not a route to try to beat personal records, or to rush. It is ideal for enjoying the journey as well as the beaches, the light and the sound of silence. It is route to be taken little by little, savouring every step along the way, every section and every centimetre of the living natural surroundings.

You need to be aware that we are heading to some secluded beaches sandwiched between huge vertical cliffs, as beautiful as they are dangerous. Depending on the time of year chosen for the walk, nature will provide in winter a pebbly beach with the hard, cold Atlantic Ocean crashing in at wintertime, while in summer a sandier beach dotted with stones with a more benevolent, less threatening and violent ocean, with gentle water that allows for a comforting bathe.

With the tide out, we will have no trouble reaching the beaches at Playa de Enmedio and Guguy Chico. It is important to choose the day carefully and monitor the tides, as we may get cut off on these beaches, with no possible exit, except by sea and by boat.

Guguy Grande is a beach that has fresh water all year round, which oozes out of the cliffs and falls all the way down, landing gently on the beach below, its volume depending on how much rain has fallen over winter. Small waterfalls may even spring up, pouring their water out directly into the sea following periods of significant rainfall. Specifically, after wet winters two little waterfalls form, one at Playa de Guguy Grande, at about four metres altitude, and other, higher up, between six and eight metres, at Guguy Chico.

Another of the charms of this route is the sheer diversity on offer. If the walk is done in summer, the landscape is arid and dry, while in winter it is awash with green, always with the beach as a climax. It is true that the beaches are not the only objective, as the route as a whole is an amazing gift for the senses, with its high-walled massifs, ravines and majestic Atlantic water with the peak of the Teide mountain in Tenerife in the background.

There are breath-taking drops with ravines slotted in between, with cardon and tabaiba plants and even a number of threatened endemic species, such as the cabezón, birds that nest on steep cliff edges, sandy or pebble beaches, and crystal clear and clean water… a full set of wonders that invite hikers to walk unhurriedly, to bask in the sheer greatness of the surroundings and to take away some truly memorable experiences.

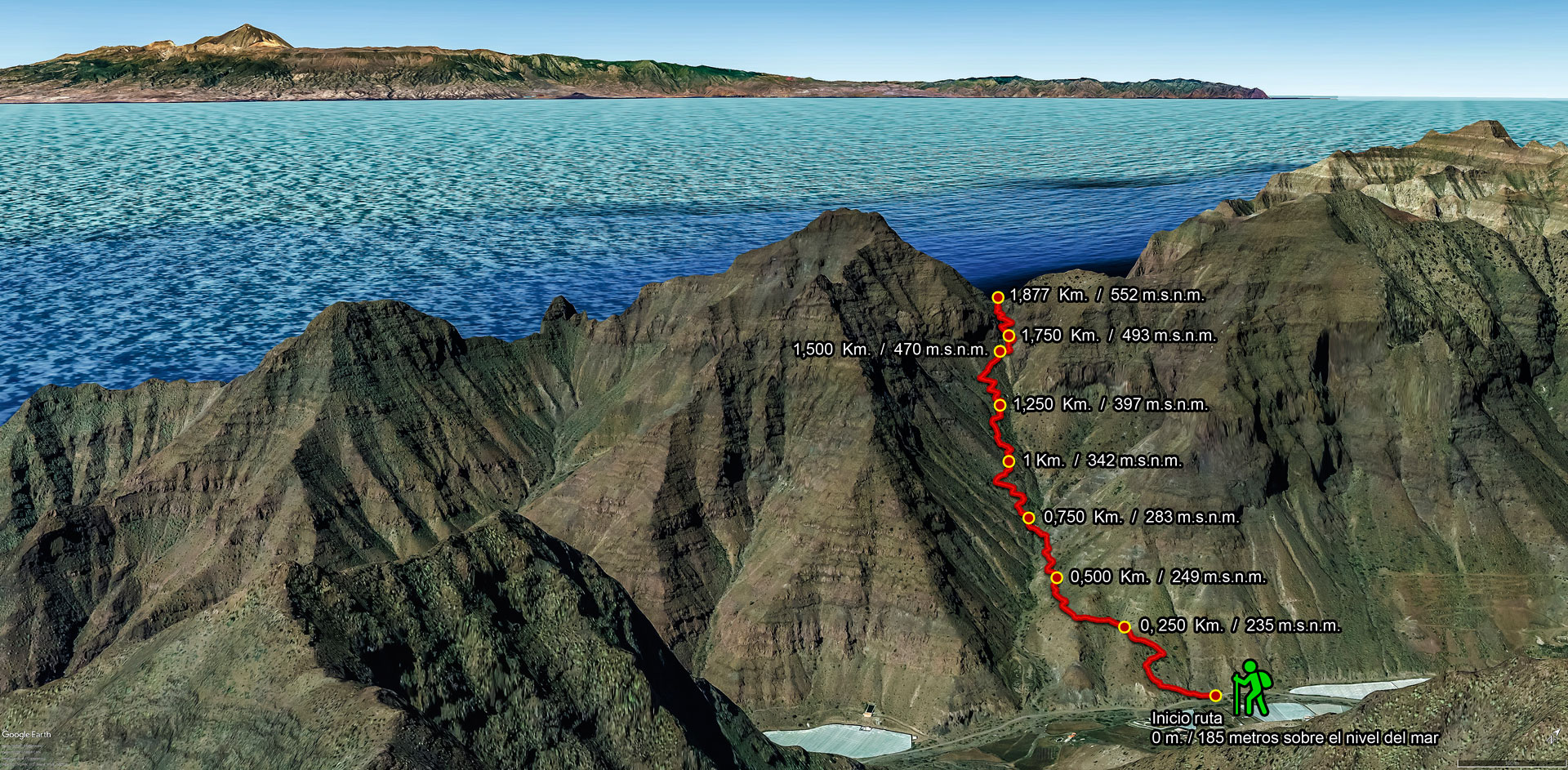

Start of the route – Section 1

The ascent can be done in under two hours, depending on your fitness, what you are carrying, how much you stop for breaks or to take photos, and how hot the day is.

The start is easy to see, as we look out to the coast we can see a signpost which marks out the start of the route and reminds us that we are entering a protected area. The footpath stretches out ahead of us as we start the climb up a small hill, taking us to the right hand side of the valley for around 700 m with a gentle slope and other flatter areas, which provides a warm-up until we reach the ravine bed at Barranquillo de Aguasabina.

Opposite us is a rocky mass and the footpath seems to peter out, and as we look over the gorge to our right we will see some boundary markers (indicating the way with several stones piled up on one another) which will once again position us on the route which zigzags along the opposite hillside (on the left hand side of the ravine as we go up). Tabaibas, enormous cardon plants and telephone masts will guide us along the way.

The ascent is a demanding one, but we need to stay calm, even though we are keen and impatient to reach the finish, and weighed down with our provisions. The climb is relentless towards the end, but we will be rewarded by some ever more extraordinary panoramic views.

The higher we get, the further away the gorge seems to be, and we climb nearly all the way to its vertical point. Here the gradient, the meandering path and tiredness all set in to make this finish stretch the toughest of the whole route. Time to get our strength back at the gorge.

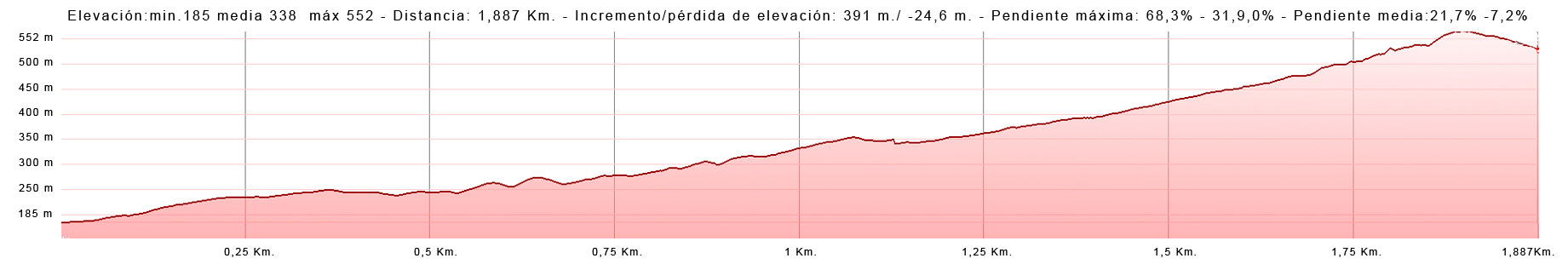

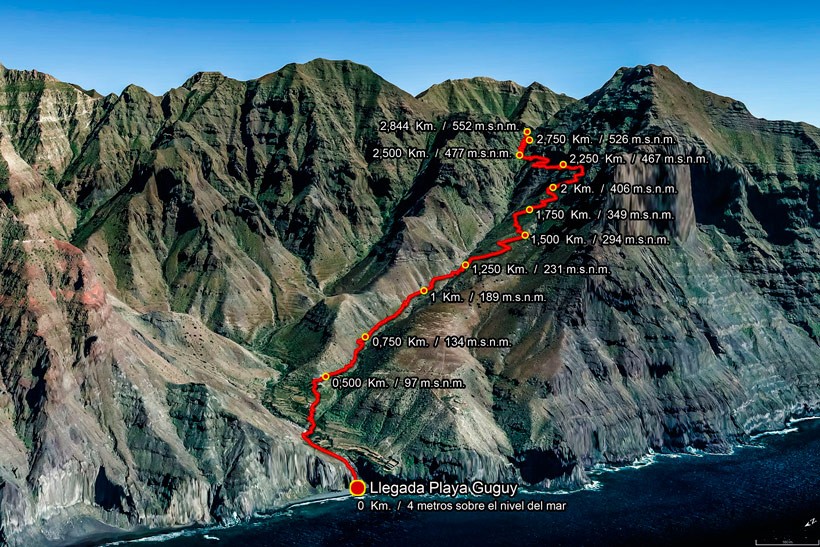

After one last effort we come to the highest point of the route, at 552 metres altitude, and before our eyes is an amazing view over the Guguy massif, with steep and sheer mountainous swathes that make up this natural setting.

Here we can take a breather, rehydrate and take a few photos or videos of what unfolds in front of us.

Section 2: Degollada de Aguasabina to Guguy beaches

Leaving behind the dry bed of the Aguasabina gorge we now make our way into the valley of Guguy with its spectacular views over the Atlantic and the whole of the mountainous massif.

From here we make our way down a winding and somewhat awkward footpath before getting to a nearly horizontal footpath along the edge of a huge cliff.

Just before we pass over the third ravine we come to the start of a large, steep hill which will take us in zigzag fashion down for nearly one kilometre, with no respite until we reach the bed of the ravine. We should take care not to slip, as the gradient will make us walk a little faster over the many loose stones on the path.

We need to pay attention at the start of the descent, as we may confuse the correct route with a faded track to our left which used to go to the ‘casa del suizo’ (house of the Swiss man), so we need to avoid it, and follow the more trodden route. We must stick to the footpath and not dabble with any short cuts.

As we make our way down and cross the ravine, some 100 metres ahead we come to a crossroads with a signpost, we need to take the path down to the left, the other path would take us towards Media Luna and La Aldea.

The descent now evens out for around 800 metres as far as a pool and the house of María Pestana, where we then come to another signpost which indicates the way to the beaches and the turning off to La Aldea.

We continue to descend for a further 275 metres through some farming terraces before reaching the ravine bed of Guguy Grande. Here we head left to cross past some canes growing along the edge of the bed for some 250 metres with palm trees and reed-beds signifying that we are on the slope down to the beach.

The beaches:

After going down the final steep and stony ramp, we now step onto the dark sandy beach of Güigüi Grande (which, curiously, rather than ‘grande’ is the smaller of the two).

The first thing that might surprise us at such a dry and inhospitable spot is the fresh water at the foot of the beach.

To our left, water oozes out of the scarps directly onto the moist sand of the beach, and to the right there is a hose to wash ourselves down with fresh water from the ravine itself.

Be careful when drinking this water, it is not guaranteed to be safe to drink, especially in periods of hot weather.

It is incredible to find a beach in the Canaries with a permanent source of fresh water right on the edge of the beach, which in rainy weather provides two cascades that fall directly into the sea.

Also take care with the sea conditions, as the prevailing currents are unknown. If you have planned to arrive at low tide in order to access all the beaches, be wary of the high tide. Passing from the beach of Enmedio to Guguy Grande over the rocks when the tide is rising is highly hazardous and you may get trapped on this beach with no escape, forcing you to wait until the tide goes out with all its consequences, such as lack of water and food… it is not recommended you take on the risky and wholly unfeasible option of climbing up the ravine wall until you reach the footpath that runs from La Aldea to Guguy.

Section 3: Return trip / way back from Guguy

This last section will take around 3 to 3:30 hours to complete, and to do it we go back on ourselves to Barranco del Asno and to the point where we started.

The return to Aguas Sabinas in summer or on hot days should be avoided when the sun is high around midday, as heatstroke is very common; the rising summer sea breeze becomes stuck between scarps, creating bands of hot air that can be quite suffocating.

It is recommended we go up in early evening, but we first need to calculate the return time and when sunset will occur. We need to ensure our arrival time occurs before the sun goes down, and add an extra half an hour or so to the trip to cover any unforeseen circumstances. We must avoid coming back at night time, although there is a margin of 20 to 30 minutes following sunset before light completely fades.

Remember that between April and September there are between 12 and 14 sunshine hours a day. The maximum number of sunshine hours are in June and July.

Once we have carefully chosen the time for our ascent, the way back is clearly marked out by the footpath and is easy to follow, although, if it is our first time, we should look out for reference points and avoid taking any short cuts from the main route, such as the turning off to Casa del Suizo or to the former Fyffes warehouse.

The start of the route back features a gentle climb, until the signpost from the footpath that comes directly from MediaLuna/La Aldea comes into view and warns us that about 100 metres ahead at the crossing of the ravine bed the toughest stage of the walk is about to start, in the form of a steep climb with zig-zags.

Once we have negotiated them and a slightly over-hanging ledge, the path flattens out, enabling us to get our strength back after such a steep and demanding ascent. This flat stretch ends with the start of the final zig-zag, this time much shorter than its predecessors, but still quite steep all the same; this is the last ascent until we reach the gorge.

From this point, we take the last descent of the route that goes down the right-hand side of Cañada de Aguas Sabinas. It is quite hard-going at first, just after leaving behind the remains of the cross in remembrance of a girl who passed away at a young age, but then the descent gradually evens out until we reach the bed of a small valley that continues to meander down the gentle slope before coming to the dirt track at Barranco del Asno, the start of the route.

Recommendations

-

Inform people of where you are going and let them know the itinerary you are undertaking

-

Do not travel alone.

-

Inexperienced hikers are advised to go with someone who knows the area.

-

This route is not recommended for people who are new to hiking or who are in poor physical condition.

-

Wear appropriate clothing and footwear, as well as a cap, sunglasses, sun tan lotion and plenty of water.

-

Avoid taking short cuts, and never stray from the main trail. If in doubt, it is always preferable to go back on yourself than to go the wrong way. People not only frequently get lost in this area but they may end with disastrous consequences.

-

Take into account that it is a very wild and isolated location. Once you have set foot in it, the only way out is on foot, by boat, or the worst case evacuation by helicopter. Mobile telephone coverage is negligible all along the route.

-

Remember that if you wish to camp overnight you need to request permission at http://cabildo.grancanaria.com/formulario-solicitud-permiso-acamapadas.

Be sure to eat and drink during the route. On all hiking routes, but especially on this route, the fight against exhaustion has to be fundamental and preventive. You must take sufficient food and drink to enable you to carry out a prolonged physical effort and to avoid situations of hypothermia and hypoglycaemia.

Hydration/Drink: Take a minimum of 3 litres of water per person (for a day trip there and back), because even though there is a natural spring, there is no guarantee that the water is healthy to drink, and there are times of the year in which it is completely dry, so think ahead, it is better to take too much water than to get thirsty on your way back. Also remember that there are no bars in Tasartico, although local residents may provide a drink if necessary.

You need to be hydrated before, during and after the route.

Keep hydrated. Avoid waiting to be thirsty, even if you are not currently thirsty, keep sipping water regularly; it is advisable to drink around 250ml every 15 or 20 minutes to prevent your stomach from feeling heavy due to drinking a large amount in one go.

¡¡¡If you feel thirsty, it means you are dehydrated!!!

Insufficient hydration at times of prolonged physical effort and a lot of sweat and heat may give rise to: muscle spasms, cramp, neurological discomfort, and in worse cases of dehydration, even death.

Mineral water, tea, juices and fruit are other good alternatives for ingesting liquids.

Eating/food: This is another fundamental aspect that you should not disregard on any route, no matter how short it may seem.

Start the route well hydrated and full of energy, in order to have vitality, strength and resistance. A hearty breakfast, rich in carbo-hydrates and fruit is essential. During the route eat regularly, making the most of the stops along the way. Energy bars, dry fruits and chocolate are foods that are easy to transport and provide high levels of energy. Half way through the route and on the beach a bread roll or sandwich is good for regaining energy, it is the best way to get back both physical and mental energy, before embarking on the tough return trip.

Waste/Rubbish: There is nowhere along the route, nor on the beaches, for throwing away rubbish, nor is there any service, boat or helicopter that collects rubbish. Remember that the sea is not a dumping ground, and burying and burning your waste is not the solution either. Any waste that you generate on the route, please bring it back with you, for your own good, and that of fellow hikers and the environment. If you pack your rucksack with provisions, be good enough to bring all the leftovers back, as they will be much lighter by then. In Tasartico or and nearby villages there are containers for putting your waste in. Do not be concerned about others leaving behind their rubbish on the beach, it is up to YOU to avoid being as ignorant as they are or even more so, and a chance to prove to yourself that you love this Earth as much as you love yourself.

When you return to Guguy, finding these beaches clean and unspoilt is one of the greatest gifts that you can give yourself. We thank you for your collaboration.

Geology and Geomorphology

The area is occupied by a central mountain range, Montaña de Hogarzales and Montana del Cedro, from which a set of deep, narrow ravines wind their way, due to intense erosive mechanisms, separated by narrow interfluves in a staggered fashion down their hillsides. The great steepness of the slopes turns into tight, narrow ravines that start at 1,000 metres altitude at source and descend down to sea level in less than 5 km.

The reserve is home to the island’s oldest volcanic cycle, and is made up of basalt formations that spread all over the region and can reach up to over 1,000 m altitude, plus extra-caldera tracheliolytic formations that are lying on earlier formations and which groups together the materials that have flowed over from Caldera de Tejeda.

There is a large quantity of dykes that cross these materials dating from the ancient volcanic cycle and which represent a sub-vertical to vertical dip. There are also sedimentary materials, which are basically Holocene dentritic and current deposits, made up of ancient alluvia and terraces, ravine deposits and beach deposits.

Bibliography: RNE GüiGüi (C-8) Jardín Canario

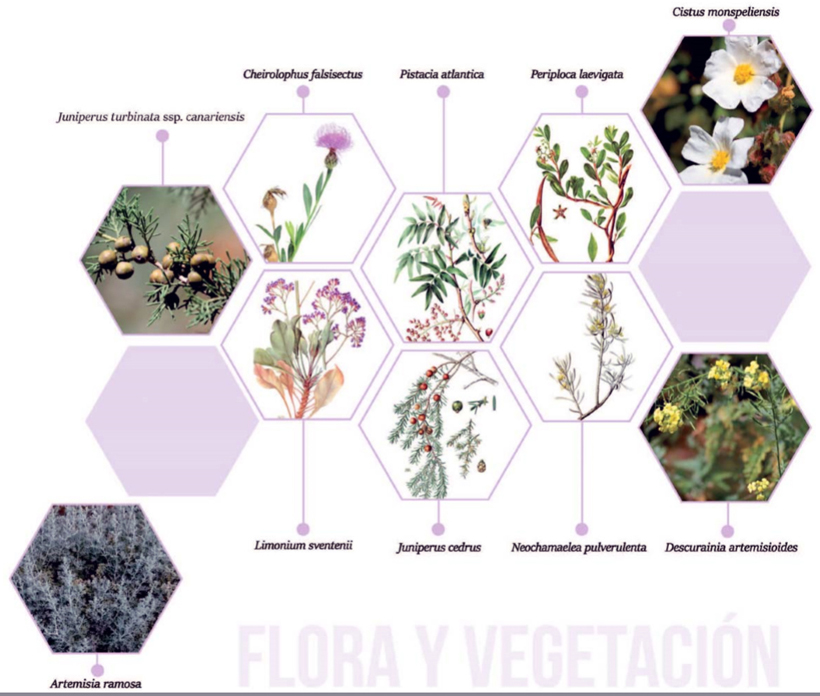

Vegetation

This space is part of Red Natura 2000, and as such has been given Special Conservation Area (ZEC in Spanish) status.

In Guguy, nearly 250 taxons of vascular plant species (native, naturalised and sub-spontaneous) have been catalogued. Macizo de Guguy constitutes an area of stunning floristic value, as it features endemic species from Gran Canaria such as Cabezote (Cheirolophus falcisectus), Corazoncillo de Anden Verde, Mostaza de Guayedra (Descurainia arternisioides) and Algafitón de Tamadaba (Dendriopoterium menendezii).

The diverse range of situations that prevail in Macizo de Güigüi (trade winds, orography, altitudes of over 1,000 metres, etc.) favour the formation of two large kinds of climatic plant-life conditions (one above 700 metres and the other below this altitude), enriched with other communities of exceptional situations, from ravine beds to humid cliffs.

At altitudes above 700 metres there are communities associated with the ancient dominance of pine trees, with a predominance of rock-growing species. On the highest ridges and cliffs, and on the small plateaus of El Cedro and Hogarzales, there are few remaining examples of Canary Pines (Pinus canariensis). The bushland that accompanies it are mainly broom (Chamaecytisus proliferus ssp. meridionalis), thyme (Microrneria lanata and Micromeria tenuis), and other endemic species such as Algafitón pimpernel, summit Magarza (Argyranthemum adauctum ssp. gracile) and summit white sage (Sideritis dagygnaphala), among others.

The lower-altitude thermo-sclerophyllous formations are typically trees and bushes such as wild olive trees (Olea cerasiformis), copperwood (Pistacia atlantica), Canary palm trees (Phoenix canariensis), savins (Juniperus turbinata ssp. canariensis) and cedars (J. cedrus). As a result of the moisture generated by the trade winds, at the highest cliffs to the northwest of the island, isolated elements appear that are linked to the transition towards Monteverde vegetation, such as heather (Erica arborea), Peralillo (Maytenus canariensis) and Laurel or Lora tree (Laurus novocana-riensis).

Linked to these thermo-esclerophyllous formations are rockrose scrubland (Cistus monspeliensis), accompanied by several different thyme species.

Below 700 metres, but which may reach up to 800 metres above sea level, standout formations include tabaibal-cardonal, with the tabaiba the most widespread, the sweet tabaiba (Euphorbia balsamifera) and cardons (Euphorbia canariensis) the main species to make up this formation. There are even examples of Tolda (E. aphylla) along coastal cliff areas, and accompanying species include the Bitter Tabaiba (E. regis-jubae), Tasaigo (Rubia fruticosa), Cornical (Periploca laevigata), Cardoncillo (Ceropegia fusca), White Taginaste (Echium decaisnei), Verode (Kleinia neriifolia) and Leña Buena (Neochamaelea pulverulenta).

Along the strip of coastline there are a number of halophyllic communities present, notably, in addition to tabaibales de tolda, other species including magarzas (Argyranthemum spp.) and Siemprevivas, such as the Amagro (Limonium sventenii).

At lower levels of altitude and down towards the beaches, there is a halophyllic strip of psammophile vegetation. In this area of vegetation, although restricted due to steep cliffs, there are small but dense groves of chamaephytes that have adapted to the marine environment. Other notable species include the Uvilla de mar (Tetraena fontanesii), Aulaga (Launaea arborescens), Salado verde (Schizogyne glaberrima) and Incienso morisco (Artemisia ramosa), among others.

When the ravine beds have temporary or regular running water, dense reedbeds (Arundo donax), an exotic invasive species, and bulrushes (Juncus spp.) spring up, together with abundant helophytic species, including carrizos reeds (Phragmites australis) and aneas bulrushes (Typha domingensis), accompanied by Majapelo (Veronica anagallis-aquatica). In neighbouring ravine beds and hillsides there are thickets of Canary palm trees, especially abundant in Barranco de Guguy Grande and Guguy Chico.

Other large extensions of plant communities also thrive in this Natural Reserve, as a result of anthropogenic activity, especially widespread shepherding, and due to the settlement of native grass communities on poorer and degraded sandy soil. In pinewood clearings and among thermo-sclerophyllous settings, typical species appear, such as Hierba turmera (Tuberaria guttata), Graminea (Aira caryophyllea or Asterolinon linum ssp. Stellatum) as well as mountain slopes with the presence of Cerrillo peludo (Hyparrhenia hirta), Cerrillo (Cenchrus ciliaris), and Aristida adscensionis and on pastureland, with the dominating presence of the fine grass Cerrillo blanco (Tricholaena teneriffae).

Among nitrophilic communities or in ruderal (wasteland) areas, common plants include the Barrilla (Mesembryanthemum crystallinum), Tebete común (Patellifolia patellaris), Patilla (Aizoon canariense) and Aceitilla bermeja (Eragrostis barrelieri), nitrophilic communities of Cenizo común (Chenopodium murale); fleeting esparto species such as Japito (Stipa capensis), Cucharilla (Carritchera annua), Yesquerilla canaria (Ifloga spicata), Maravilla africana or alada (Calendula aegyptiaca) and Romerillo pardo (Oligomeris linifolia) and finally on ridges and hillsides where there is little cattle activity, species formed by la pegajosa (Drusa glandulosa) and la Ratonera ocucha (Parietaria debilis).

Sources and Bibliography: Bibliography: RNE GüiGüi (C-8) Jardín Canario

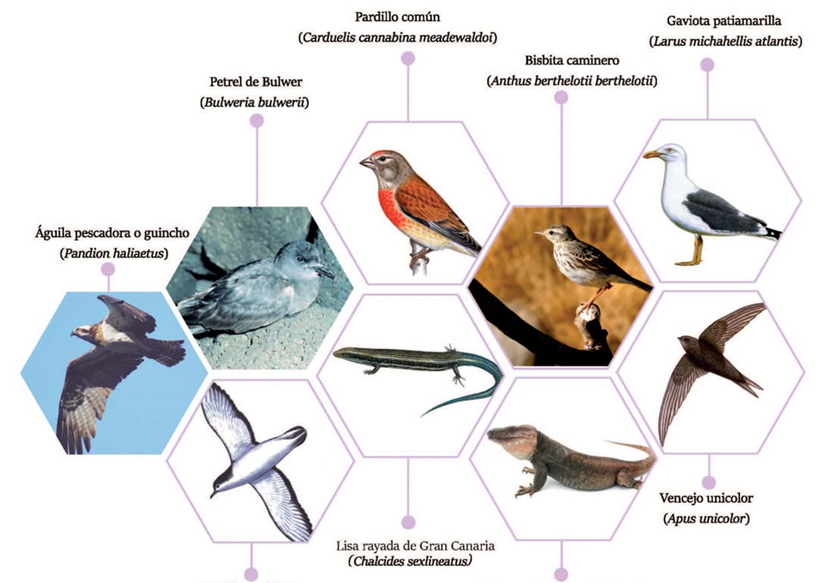

Fauna

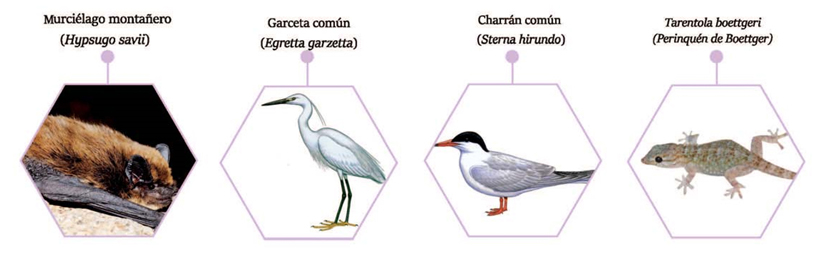

Amphibians are represented by two species; the green frog (Hyla meridionalis) and the common frog (Pelophylax pereziz).

These can be found in areas where they can access water in order to reproduce and a damp enough environment for their daily activity, such as ponds or puddles in ravines.

Reptiles constitute a highly interesting group within Canary fauna. In this natural area there are three species that are endemic to Gran Canaria: the giant lizard of Gran Canaria (Gallotia stehlinii), which inhabits ravines, farmland crops and stony plains, the Lisa de Cran Canaria (Chalcides sexlineatus sexlineatus), also known as the (striped) Lisa rayada, which lives in concealed and stony spots, and can be found from sea level up to altitudes of 700 metres approximately, and finally, the Boettger’s wall gecko (Tarentola boettgerii boettgeri), which can be found in and around stones in inhabited areas.

Birds constitute the largest group of vertebrates in the reserve, which contains a large variety of Canary ecosystems, from the halophytic coastal strip and the cardonal-tabaibal region to areas of thermophilic formations, namely Monteverde and pine forests. This great diversity of landscapes brings with it a large quantity of different species associated to these ecosystems.

Of the species linked to watery locations along ravines, the most notable are the rock dove (Columba livia livia), the Canary blackbird (Turdus merula cabrerae), the grey wagtail (Motacilla cinerea canariensis) and the robin (Erithacus rubecula superbus).

Linked to anthropised areas and down ravine slopes are the rock dove and the grey wagtail, highly common at Barranco Tasartico; the robin (Erithacus Rubecula superbus), the Canary kestrel (Falco tinnunculus canariensis), flying over the pasturelands; also regularly spotted is the common turtledove (Stneptopelia turtur), the hoopoe (Upupa epops), the pipit (Anthus berthelotli berthelotii), the partridge (Alectoris rufa), the Canary Islands chiffchaff (Phylloscopus canariensis canariensis), the goldfinch (Carduelis carduelis parva), the common greenfinch (Carduelis chloris aurantiiventris) or the common linnet (Carduelis cannabina meadewaldoi).

Most species use the beaches and low-lying coastal areas only occasionly and for a resting or sleeping area (seagulls), due to their low levels of interaction with man. The species to use this environment include the little egret (Egretta garzetta), the whimbrel (Numenius phaeopus), the Kentish plover (Charadrius alexandrinus), the little ringed plover (Charadrius dubius), the sanderling (Calidris alba), the dunlin (Caiidris alpina), the common tern (Sterna hirundo) and the yellow-legged gull (Lanus atlantis).

One of the finest environments for the reserve’s birdlife is the clifftops, in terms of their suitability as nesting areas. The most common bird here is the yellow-legged gull, which nests in places such as El Descojonado. Nesting in the area around Peñón Bermejo, Llanos del Mar and Las Estaquillas is the Cory’s shearwater (Calonectris diomedea borealis). Osprey and lapwing (Pandion haliaetus) nests have also been spotted just metres above sea level, to the south of Playa de Güi Güi Grande. The Barbary falcon (Falco pelegrinoides) also nests in the region, while regarding the possible nesting of the common storm-petrel (Hydrobates pelagicus), and Bulwer’s Petrel, there is no precise data to prove their presence, although potentially the cliffs are an ideal nesting site for both species.

Of the species linked to the areas of steep ravines, containing many caves and cracks that provide superb nesting sites, we can point to many different types: the common buzzard or Canarian eagle (Buteo buteo insularum), which is present nearly all over the island; the long-eared owl (Asia otus canariensis); the crow (Corvus corax canariensis); the plain swift (Apus unicolor) which builds its nest with straw and feathers on vertical walls; the trumpeter finch (Bucanetes githagineus amantum) which nests in isolated rocky locations; the Canary kestrel, the most common bird of prey on the island and on the reserve, which inhabits from the highest levels of the island all the way down to a few metres above sea level; or the rock dove.

Species that live mainly in scrubland, cardon and tabaiba regions include the spectacled warbler (Sylvia conspicillata orbitalis), the southern grey shrike (Lanius meridionalis koenigi), the trumpeter finch, the Berthelot’s pipit, the partridge, the rock sparrow (Petronia petronia maderensis), the canary (Serinus canarius), the European turtle dove (Streptopelia turtur), and the hoopoe.

The most common species linked to the remaining areas of thermophilic woodland include the Sardinian warbler (Sylvia melanocephala leucogast), the hooded warbler (Sylvia atricapilla heineken), the blue tit (Parus teneriffae hedwigii) and the canary.

As for mammals, one of the most common and widespread is the Savi’s pipistrelle (Hypsugo saii). This group also includes species introduced by man which are abundant all over the island, such as the rabbit (Oryctolagus cunicuius), the North African hedgehog (Atelerix algirus), which are quite common in low-lying farmland, although is more widespread due to their low requirements for locating their habitat.

As for rodents, the most common are mice (Mus musculus) and rats (Rattus spp), introduced by man involuntarily, and which represent the most negative effect on the region’s wildlife. This area also has other foreign species which remain in a wild state; this is the case of the goat (Capra hircus) which is very harmful for vegetation and the cat (Fells catus) a predator of endemic birds and reptiles.

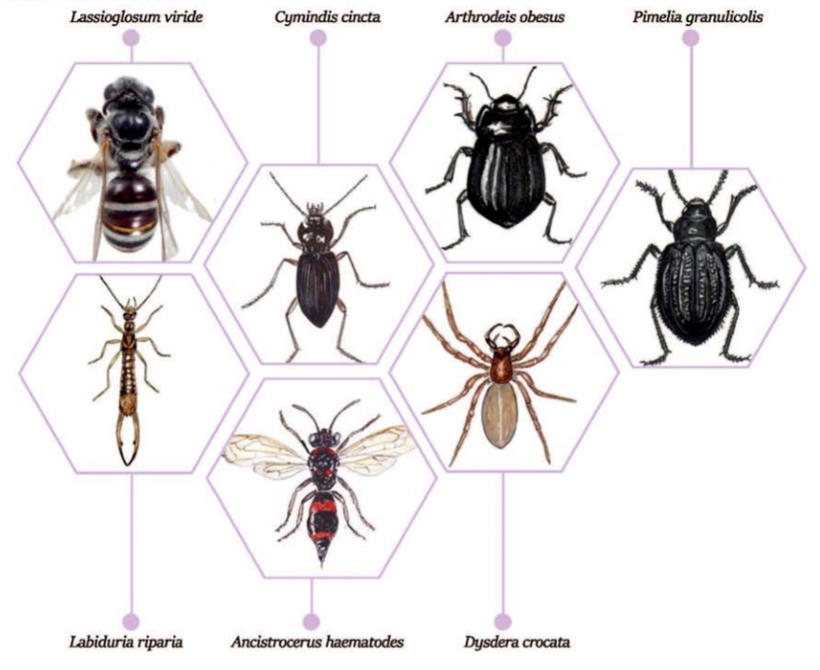

Invertebrate fauna

Invertebrate fauna is widespread and extremely varied in Gran Canaria. They include a good number of endemic species from the island, from the Canary Islands and a few others that are widespread around all the islands.

Gastropod molluscs are represented by the Chuchanguita snail (Napaeus josei), an endemic species exclusive to Gran Canaria. Nematodes are present in Meloidogyne javanica, a widespread species.

The island’s endemic arachnids include, among others, the Bandama dysdera (Dysdera banclarnae), the Los Tilos dysdera (Dysdera tilosensis), Zygoribatula laubieri canariensis, Oecobius tasarticoensis and Neoseiulella splendida. Canary species include Calyptophthiracarus canariensis and Hermanniella laurisilvae. Other species range from the citrus spider mite (Aleurodaniaeus setosus), Odonto cepheus elongates, Zygoribatula frisiae, to the invasive dysdera (Dysdera crocata) which are widespread.

Insects are very well represented in this Natural Space, the most abundant of which are beetles. Endemic species from Gran Canaria include the magarza weevil (Cyphocleonus sventeniusi), the Gran Canaria boliche weevil (Arthrodeis obesus crassus), the Chispita de La Aldea (Attalus aldeae), the black beetle (Hegeter impressus), the Pimelia de las arenas (Pimelia granulicollis), Cymindis cincta, Gonocephahun merensi estevezi or Hegeter webbianus, among others. Canary endemic species include the Carnerito de tabaiba (Deroplia albilla), Carnerito anillado (D. annulicornis), Cucarro boliche enano (Arthrodeis curtus), Cucarrito correlón (Zophosis bicarinata bicarinata) or the Cucarro del cardón (Pelleas crotchi).

Dermaptera insects present a wide range of species such as the tawny earwig (Labidura riparia) or the sheep bot fly (Oestrus ovis). Canarian hemiptera species include the common bee (Lasioglossum viride), Andrena mediovittata arvensis, Hylaeus hohmanni, Leptochilus cruentatus, and other common species such as Ancistrocerus haematodes rubropictus, Corynis sanguinea and Cnossocerus lindbergi.

The class of malacostracan amphipods include an endemic Canary species, namely the Melita de fuente (Pseudoniphargus fontinalis).

The millipede (Dolichoiulus architheca) is also an endemic species from Gran Canaria.

Intertidal area: limpets, Burgao snails, Moorish red-legged crabs, caboso fish, barracudas, prawns, starfish, Algae.

Finally, many marine species can be spotted, including the common dolphin, turtle, parrot fish, and pejeverde green fish.

Sources and bibliography: Bibliography: RNE GüiGüi (C-8) Jardín Canario

Cultural Heritage

Ethnography: Ethnological assets (barns, pools, kilns, etc.) in the Reserve are mostly located in the ravine basins of Los Calderillos and Guguy Grande, and in areas near to the ravine beds.

More information: FEDAC https://goo.gl/PcuXxD

Archaeological Heritage

The area of Guguy is listed in archaeological region “C”, spanning the area from El Perchel (between Mogán and Venegueras) to Guguy Chico. According to the inventory carried out by The Canary Museum from the Archaeological Map of La Aldea de San Nicolás, important settlements are located in the area of Guguy, with notable sites being Corral de Zamora, Llano de la Mar, Andén del Paso de la Salinilla, Media Luna, Casas de Guguy Chico, Montaña Pajaritos and Degollada de Piletas, Tagoror Rojo, in addition to burial sites at Cueva Blanca.

Gastronomy

The gastronomy on offer in La Aldea is very rich and varied. Standout foods include fresh fish and seafood, meat, fish broth with gofio cornmeal, moray eel spicy mojo sauce, stews, etc.

A special mention should go to a dish created in this municipality: Octopus Ropa Vieja. Tropical fruits also abound: Canary bananas, papayas, avocados and mangos. Also available are exquisite home-made jams made with tomatoes, papaya, mango, and local pastries made from the same fruits, including dulce de mango, dulce de papayo, queques spongecakes, buns and mantecados rolls.

Cheese made in La Aldea are of a very high quality, as demonstrated in their success at cheese competitions where they have won awards thanks to their extraordinary flavour. An example of this is “La Colina” cheese.

IMPORTANT: The information contained in these routes is for guidance purposes, which exclusively seeks to encourage sporting activity in natural surroundings and educational country walks. The Town Hall of La Aldea de San Nicolás provides this information for the benefit of users of this website, and waives any responsibility as to the current state of the routes, offer, quality and ownership of the areas that walkers pass through, etc.

Likewise, the Town Hall is not responsible for any errors, omissions, or for a user of this website going off course and suffering an accident. Hikers are reminded that they access these mountainous areas voluntarily and with informed consent, that is, each person should be responsible for their actions.