Route description:

We shall be walking along the ancient royal footpath that joined La Aldea de San Nicolás with Mogán, crossing the ravines and gorges of Tasarte and Veneguera. 2017 marked 100 years since the Ministry of Public Works and Transport drafted the project to join the two towns with a road.

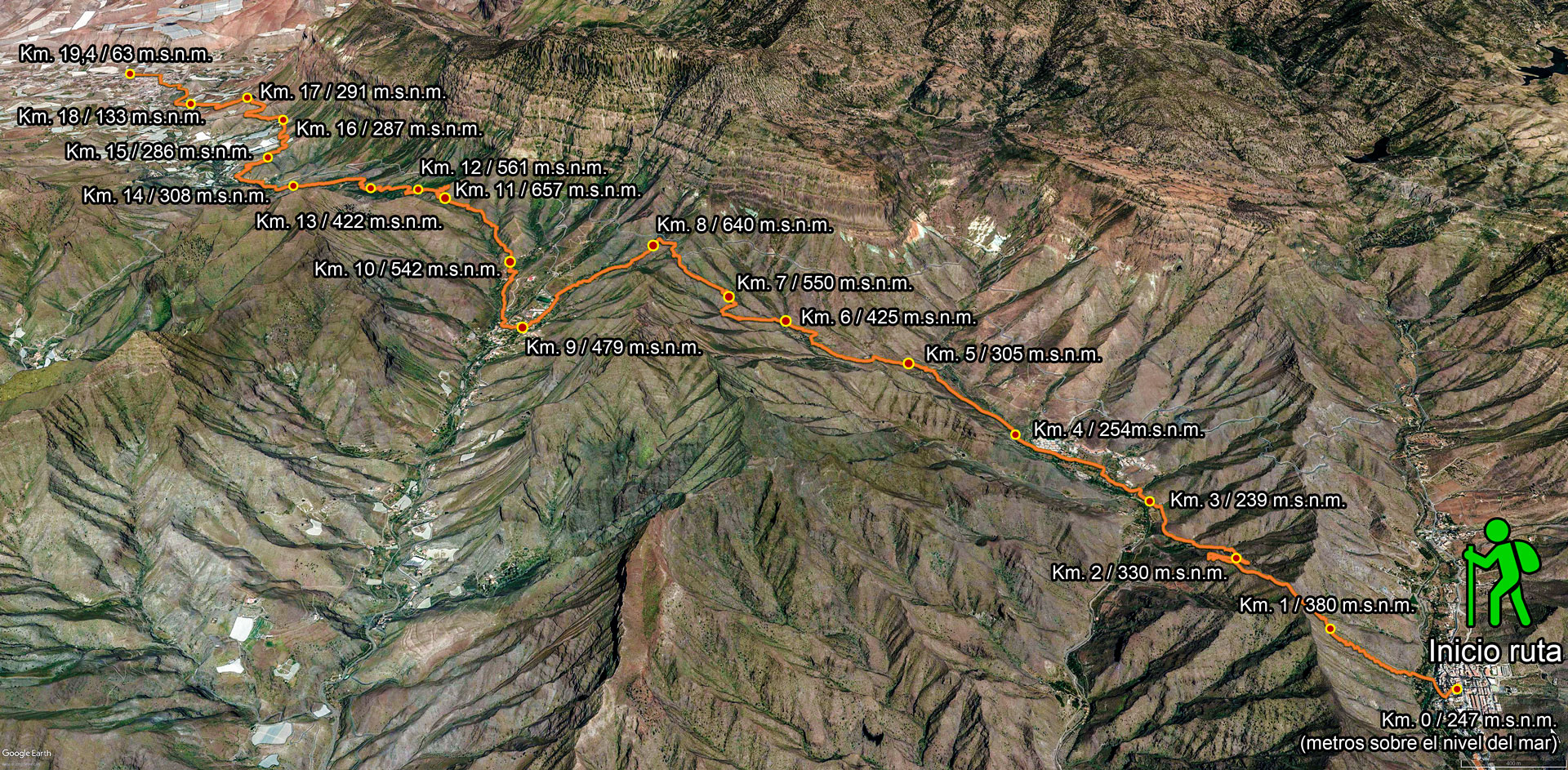

This is a near-straight route with gentle ascents and descents, but is somewhat more challenging due to the distance to be covered rather than due to the difficulty of the route itself or the places walkers have to pass through.

Its orography enables us to take in extensive panoramic views over the valley of La Aldea, Tasarte, Venegera and Mogán. The route takes us through quickly-changing settings, from arid and empty hillsides to lush palm groves, reeds and sugar canes at the bottom of ravines, and crossing farming estates with tropical fruit trees and tomato plantations.

The trail will give us a different insight into Los Azulejos, to a more arid Gran Canaria dotted with stretches of greenery and orchards bearing exquisite-tasting fruits.

Other attractions include ravines with plenty of ethnographic details including bread kilns, pottery kilns, wells and small hamlets which will whisk us away to long-forgotten times, plus thematic museums displaying settings from a bygone age.

The ideal time to do this walk is in spring after winter rainfall, as the vegetation will be blooming, its vibrant green contrasting with the dark rocks and the trickle of water running down the ravines.

As a climax to the route we can learn a little about country life in the area, through the live ethnographic museums. These include the old school, the country doctor’s practice, the oil and vinegar shop (ask for Polo’s shop, a living bastion of this type of establishments https://www.flickr.com/photos/canarias3d/albums/72157656610650948 ), the tomato warehouse, Naso’s shoe shop, the church of San Nicolás, the Locero Adelfina Cubas pottery centre, and the Water and Blacksmith’s Museum.

Useful documentary information

Cardones de Veneguera

Located on the site of Veneguera is a recreational area comprising benches, tables and shades in the form of an eco-museum display, with lemon trees, tabaiba plants and a dozen cardon bushes (Euphorbia canariensis), some of which are exceptional on the island, reaching a height of 3 metres, a perimeter of around 46 metres, and occupying an area of around 160 square metres. They are able to create a microhabitat in their interior, with a diverse range of plant and animal species thriving there.

This bush is endemic to the Canary Islands, and can live for over 100 years. They can grow as many as 400-500 stems that sprout from the base of a central bush and spread out in circles all around.

It has the appearance of a set of four-sided or five-sided curved stems in the shape of a candelabra with tiny, robust thorns on its edges.

It is a perennial bush that flowers in spring and summer with rows of flowers all along its edges.

It green-reddish flowers sprout from dull red-brown capsules at the upper end of the cardon. Its fruit is called tricoca, and is capsule-shaped with three reddish-brown valves that shoot the seeds out powerfully.

It grows at altitudes ranging from 100 metres to 900 metres above sea level in sunny locations and on well drained land. It grows on all the islands except for Lanzarote. It is an endemic plant species of the Canary Islands and a true symbol of the island of Gran Canaria.

Beware: the cardon plant contains latex, a thick, white caustic sap. It is quite toxic and highly poisonous if it is ingested or comes into contact with the skin or the mucous membranes. This latex used to be used in fishing by pouring it into pools of water to fluster the fish, in a technique known as embarrascado that nowadays is banned. It is also claimed that aborigines in times of drought were able to separate the toxic bark in order to obtain water from the cardon’s inner pulp.

Casas de Veneguera

A small ensemble of old houses dating from the 17th century, built in traditional Canary architectural style; stone, mud, lime and wood on doors, windows, balconies and roofs covered with gabled tiles.

There is also a traditional bread kiln located there. These austere and above all functional dwellings are a fine little example of traditional Canary architecture, and the kiln was the central hub for the hamlet.

Fuente de la Sabinilla

A natural water source that flowed out from a rock and provided water for a trough and laundry area nearby, with room for 12 washing sinks. It is estimated that it has been a laundry for 150 years.

Roque y Casas de la Cogolla

This basalt rock is located at the end of the ravine of the same name, and features some curious geological shapes. To the west and looking southwards, we can make out the profile of a little Joker-type face, with a long pointy nose. If we view it from its northern side (depending on whether we are going up or down the track that takes us to the houses) we can see three caves set out in a triangular formation that resemble two eyes and an open mouth with a surprised expression, above which is silhouette in the shape of a hood covering the head. Its name may well come from its similarity to the hood worn by religious monks.

Whether as a geo-formation or an isolated rock, it seems to act as a look-out for the little set of houses at Casas de la Cogolla. They provide another display of Canary country houses along the route, made out of stone and tiles, with barns, pools and a bread kiln. They are accompanied by an abundance of Canary palm trees, a lush grove that sprouts up alongside the terraces of crops. This place is well worth a visit in spring time.

Tile kilns in Tasarte

Today there are three kilns. Their walls are made of stone and rubble, and are truncated cone-shaped, lined with a clay mortar and whitewashed with lime. They are around 5 metres in height and have an orifice at the bottom for stoking the fire and another orifice at the top where tiles were placed and heated up.

In the areas of Las Gamonas, Las Charquetas and El Ojo del Agua, there were once tile kilns where they made all the tiles for the houses in Tasarte.

These kilns had and still have owners, but they didn’t always make their own tiles with them, but often lent them out to neighbours so that they could make their tiles too. Two men are remembered even today for their skill and craftwork making tiles.

The mud used to make tiles was coloured, and for the colour to be acquired it had to undergo a lot of heat. The mud was previously sieved to eliminate stones and other impediments. The mud was then made into a paste with water, to which salt and sulphur were added. Salt was used in this process because when it melted in the heat it produced water that gave the tile a crust, preventing it from splintering due to the high temperatures it was subjected to in the kiln. The sulphur was used to enhance the colour of the tile. Once all the components were prepared for the paste, mud, water, salt and sulphur, it was kneaded constantly with the feet until the paste began to resemble a belt. Then a piece of mud was spread over the paste in order to smooth it over a mould that the men used to make the tiles with. Once the mud spread over the mould it began to dry out. There are also testimonies of the early days when the mould used to shape the tile was actually the thigh of the person making the tile.

The tile was then put into the kiln, making sure it was placed vertically, as if it was placed horizontally, and other tiles were place upon it, the bottom tiles would get squashed by the weight and its baking would not be achieved evenly. Once all the tiles were in the kiln, the fire was lit, the fuel used in the early days was firewood and stubble that were collected from hillsides and ravines in the area, then later on the fuel used was quicklime. When the fire turned blue in colour it meant that the tiles were properly baked.

In this area, the highest in the neighbourhood, the tiles were transported either by donkeys or on labourers’ shoulders to where houses were being built.

Around this time neighbours would work together, for carrying tiles and also stones on the donkeys or on their shoulders for house building. This collaboration lasted for years, even when houses were built in a more modern style, as neighbours would work together to place concrete blocks and to help with building roofs.

English tiles began to gradually replace those made in Tasarte until houses began to be made with flat rooftop terrace tiles.

Today the kilns have been declared an ethnographic heritage.

Bibliography: Tasarte Blog http://bienvenidosatasarte.blogspot.com.es/2013/10/hornos-de-teja-en-tasarte.html

Live ethnographic museums

As a climax to the route we can learn a little about country life in the area, through the live ethnographic museums. This include the old school, the country doctor’s practice, the oil and vinegar shop (ask for Polo’s shop, a living bastion of this type of establishments https://www.flickr.com/photos/canarias3d/albums/72157656610650948 ), the tomato warehouse, Naso’s shoe shop, the church of San Nicolás, the Locero Adelfina Cubas pottery centre, and the Water and Blacksmith’s Museum.

Vegetation

This route is dominated by Canary coastal xerophytic vegetation and thermophilic woodland.

A feature throughout the route are the cardon and tabaiba plants, together with verodes, taginastes balillos, balos, tasaigos... and other introduced plant species and associated with farming activities, including tunera cactus and pitas which were planted to mark out the boundaries of the fields. At the bottom of the we can find some outstanding palm groves, wild olive trees, tarajales, reeds, canes and sage and other associated species.

Fauna

Along this trail we will come across three endemic species from the island: the Gran Canaria giant lizard (Gallotia stehlinii), which inhabits the ravines, farming crops and stony fields, the Gran Canaria skink (Chalcides sexlineatus sexlineatus) and the Boettger wall gecko (Tarentola boettgerii boettgeri), which can usually be found under stones and in inhabited areas.

Among the birds that can be spotted are the Canary kestrel (Falco tinnunculus canariensis), partridge (Alectoris rufa), and the Canary crow (Corvus corax canariensis) plus many other species.

IMPORTANT:The information contained in these routes is for guidance purposes, which exclusively seeks to encourage sporting activity in natural surroundings and educational country walks. The Town Hall of La Aldea de San Nicolás provides this information for the benefit of users of this website, and waives any responsibility as to the current state of the routes, offer, quality and ownership of the areas that walkers pass through, etc.

Likewise, the Town Hall is not responsible for any errors, omissions, or for a user of this website going off course and suffering an accident. Hikers are reminded that they access these mountainous areas voluntarily and with informed consent, that is, each person should be responsible for their actions.